The Pilgrims of Plymouth and their Puritan comrades of Massachusetts Bay had founded their colonies in the midst of the vast, trackless, New England wilderness. We are all familiar with the desolation of the Pilgrim community during that first fateful winter in the New World and sadly there were others like it. North America, in its natural state was merciless to Colonists from Europe. It was the helpful guidance of Native Americans that preserved these colonies through those first few years until they became increasingly self-reliant. The Pilgrims had established good relations with the Native American nations in the Plymouth region. The Natives and Settlers had even feasted together in 1621. However, after William Bradford and Massasoit died, their peoples grew distant and more hostile to each other.

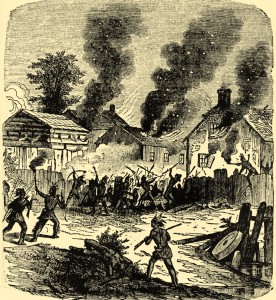

It was fifty-four years since the first feast in 1621 when warfare broke out between Massachusetts and the Wampanoag nation and their allies. The Wampanoag were led by their sachem Metacomet, the son of Massasoit. The English called him King Philip. The bloody conflict between the two, known as “King Philip’s War” lasted from 1675 until 1678. The war was of the usual frontier fare, complete with massacres, village burnings and ambushes. The two sides were instigated to war because of long-held tensions and disagreements. In June, 1675, three Native Americans were executed for the death of John Sassamon. The Pokanoket nation prepared for war and soon began looting the abandoned town of Kickemuit. Many colonists retreated to garrisons across the colony and the English began scouting around the area. They then split their forces. Benjamin Church, Samuel Fuller and their men were transported by boat from Mount Hope Neck, Massachusetts to Pocasset. Fuller went north, Church went south. Church had lived among the Sakonnet nation in Southern Pocasset for some time and had established a friendship with the female sachem Awashonks. He headed towards the Sakonnet nation in an attempt to persuade them to side with the English. On the way, he and his twenty men were passing through a pea field when they were ambushed. They retreated to a sunken, stone wall and held their ground. (Church was one to hold his ground. He had charged the enemy earlier during a sortie from the Miles garrison. One could say that he was, at times, reckless.)

The Pease Field Fight, as it became known, continued as hundreds of Native Americans fired at the small line of colonists. Church ordered his men to take off their coats so that any passing ship coming down the Sakonnet River would recognize the white shirts of the Englishmen and come to their relief. Eventually, Captain Roger Goulding came sailing up the river in a small sloop. He anchored and sent a canoe to help the colonists withdraw to the ship. Slowly, yet surely, the colonists escaped, two at a time, in the canoe. Church was the last to leave. He was boarding the canoe when he remembered his hat and cutlass back at the stone wall. Despite his comrades’ pleas he leapt out of the canoe and rushed to get his gear. He was the only target that the Natives were shooting at. Still, he was not hit. He reached the sloop unharmed, thanking the “glory of God and His protecting providence.”

A similar episode would occur eighty years later at the Monongahela River during the French and Indian War. George Washington would escape a French ambush unharmed, despite having two horses shot from under him and multiple bullet holes in his hat and coat. Some things, many things for that matter, are not coincidences. They are evidences of the providence of God.