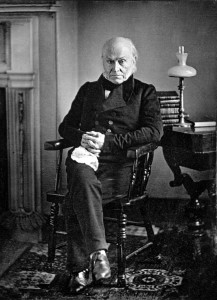

In honor of President’s Day, I will be highlighting one of my personal favorite Presidents: John Quincy Adams. Arguably, John Quincy Adams was one of the worst Presidents in American history. His administration was a failure and he along with his father, John, were the first two Presidents to be denied a second term in office. Despite all this, John Quincy Adams remains a towering figure in the history of the Early Republic because of what he did before and after his brief time in the WHite House.

Born in 1767 in Braintree, Massachusetts, to John and Abigail Adams, young John Quincy was destined for great things from the cradle. He lived in the shadow of his great patriot father and accompianed him on several diplomatic trips to Europe. In 1775, he watched the battle of Bunker Hill with his mother from a nearby hill. This was John Adams’ fight for freedom but John Quincy would have ample opportunity to fight for the same in his own life. After accompianing his father on diplomatic missions to Europe, John Quincy received a diplomatic commission of his own at the age of twenty-six, appointed by President Washington to the Netherlands. Before this, he had travelled across Europe as a translator and secretary. Diplomacy was one of John Quincy’s great God-given gifts and he used it nobly and powerfully for the good of his country.

In 1803, John Quincy took a seat in the United States Senate. He was appointed by the Federalist-controlled Massachusetts legislature (state legislatures chose Senators back then). However, he quickly made many enemies in the both the Senate and back home in Massachusetts by supporting the policies of the Democratic-Republican President Thomas Jefferson. The ardent Federalists in Massachusetts, led by John Adams’ rival Timothy Pickering, now John Quincy’s counterpart in the Senate, villified John Quincy. The Federalists hated him because he supported Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans hated him because he was a Federalist. Adams quickly found himself on a political island amidst a churning hurricane of hatred. Adams resigned his Senate seat in 1808 due to pressure from the Massachusetts legislature.

The next chapter in Adams’ life would involve more diplomacy. He lead the American delegation to the Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812. He was appointed as Secretary of State by President James Monroe and in this position, strengthened America’s diplomatic corps and drafted the landmark “Monroe Doctrine”. In 1824, John Quincy ran for President, the office his illustrious father had occupied for one term. The contest came down between Andrew Jackson, a Tennessee war hero and Democratic-Republican, William Crawford, another Southern Democraic-Republican and Adams. The election was decided by the House of Representatives because none of the candidates received the required majority of electoral votes. Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House, thwarted the populist Jackson in the House and Adams was chosen in what Jackson’s bitter supporters called a “corrupt bargain”.

Although Adams was a strong and capable leader, his Presidency was plauged with the machinations of his enemies, namely Jacksonian Democrats. As a result of John Quincy’s firmly stubborn personality and his enemies’ equally stubborn opposition, President Adams’ term was unimpressive. In 1828, the Jacksonian faction stormed back in a vengeful seizure of the White House. Jackson beat Adams and John Quincy’s first term was confirmed to be his last. However, unlike most Presidents, John Quincy’s story does not end there.

Perhaps the most dramatic and heroic years of Adams’ life were lived after he left the Presidency. He was elected to serve Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and he held this office until his death in 1848. During his career in Congress, he became known as a strong and sometimes solitary voice against slavery. Nicknamed “Old Man Eloquent”, Adams stood for abolition even when he stood alone. When the Southerners in Congress passed a “gag rule”, forbidding petitions from the people to be brought up in Congress, Adams fought it almost singlehandedly. Eventually, the gag rule was eliminated and the “right of petition” emerged from the ring victorious. Adams stood firm and unwaveringly on his convictions but was also capable of compromise. In the Nullification Crisis of 1828, it was Adams, who brought the conflict over tariffs to an agreeable end through a compromise that he crafted to satisfy both sides of the struggle.

In 1848, Adams’ health was deteriorating but he continued serving Massachusetts and the United States in the House. It was during an particularly dramatic speech on the House floor that he collapsed and died soon after. Widely regarded as one of the greatest diplomats in American history and a great voice for abolition in the antebellum Congress, John Quincy Adams left a legacy as extensive as his father (which is saying quite a bit). More than the bills, legislative victories and documents he left behind, he left a heritage of character. A man who was not afraid to stand alone in the midst of th hostile arena, like a Roman gladiator in the Colisseum, his bravery is not easily paralleled. Upon his death Elizeabeth Whittier wrote these words in his commemeration: “So well and bravely has he done the work he found to do, To justice, freedom, duty, God, and man forever true.”